How Not to Make a Podcast (Episode #2)

Before I started the Conde project, I collected some proof of concept stories— Si Newhouse's sleepy introduction to the iPad, a mid '90s email ban from Vogue leadership, and more. This could be fun.

I wouldn’t exactly call it a gold rush—I mean, these are podcasts I’m talking about—but five years ago people were buying series of the sort I was trying to make. Narrative, non-fiction storytelling. While the studios definitely favored strong A-character plots—ideally involving forensic reports and slipshod detective work executed by some short-sighted lackey working for some impenetrable, ideally bigoted institution—I thought I could interest them in an oral history.

After all, an oral history that tracked the rise of four or five editors in chief while also bringing in dozens of supportive, wildly colorful characters to help tell their stories and capture a golden age of magazines wasn’t so uncommercial, was it? And it wasn’t just the editors I’d talk to: I’d get the journalists who covered the palace intrigue, the publishers who supported them and occasionally tried to get them fired, the assistants who kept their secrets. It would be a series not just for anyone who worked at Conde Nast, but for every magazine-loving kid who showed up in New York after 2007 feeling like they'd just missed the party. The hostess was crying in the bathroom with the last bottle of tequila and the neighbors had called the cops. The worst part for the newcomers, they could tell—from the empties and the state of the fleeing guests—that the party had been epic.

The show’s appeal would be the slow reveal of the true nature of the place by weaving together disparate voices all recounting different experiences. And not everyone who worked at Conde Nast had the same experience: the memories of an assistant fitness editor at Self are not the same as those of a Market Editor at Vogue. For many, working at Conde Nast made them feel invisible, others were treated like royalty.

The Conde Nast story was not just about its history cultural impact, though that was part of it, but about the company as a creative catalyst. It was about the people whose lives were changed by having worked there. The magazine business in general, and Conde Nast in particular, offered a portal to a more interesting life. Because if you were a middle class kid from an unremarkable American suburb, working at Conde Nast was a path to a semi-glamorous New York life. It would put you closer to the flame. You would know the right people, go to the right places, meet and even collaborate with your heroes. If nothing else, Conde Nast made editing a magazine look like the most fun job in America.

The point was to hear from the people who had the fun while it lasted.

I started small. As a proof of concept, I interviewed a few people I knew would be game. A guy whose flame burned bright as a 30-something editor in chief. “You feel you’ve just been anointed,” he said. “You get to wear the crown. It felt amazing.” He also told me about his short, unhappy stint at Vogue in the early 90s, and being scolded via fax by his new boss for sending an email introducing himself to his new colleagues. "We don’t send email at Vogue. It’s rude.”

I interviewed a friend who recounted watching a colleague introduce Chairman Si Newhouse to the iPad. For the first time, Si was experiencing one of his magazines on the iPad, the device that was going to save magazine publishing. “It was late afternoon, and the music was tinkling and Si was being encouraged to to flip through the digital pages of Wired on the iPad. In a couple of minutes, it was clear Si was asleep and I kind of quietly slipped out of the room.”

Obviously, part of the story would be about the company’s sluggish, contemptuous approach to digital, but it would also be about the entitlement and ridiculousness of it all: the editor who used the company’s FedEx to shipped home the rugs she bought in Turkey, the editor who found a way to expense their kids birthday party, the 110 staffers flown out to LA for Vanity Fair’s Oscar party.

But even the less outrageous stories felt like they came from a different time and world entirely. Besides, everyone sounded great. And that was just the few people willing to talk to me as a favor. What would happen when I started going after the people I didn’t know? What kind of stories would that yield?

So I put together a little trailer, a proof of concept—three or so minutes of the early highlights, which I included with the written pitch I emailed around. I don’t know how many people actually listened to it, but it proved to me that the concept could work. This podcast would never be massive. Lots of people didn’t even know what Conde Nast was exactly, but the people who cared would really care. The trick would be to get and keep them hooked with wild stories and characters who’d make you forget you were driving to work, walking the dog, making shallot pasta for your family.

And then, all of sudden, there was further evidence the series could work—a podcast that proved there was interest in Conde Nast, as a workplace and as a villain.

[ Skip ahead if you already know the Test Kitchen saga.]

Gimlet Media, which had been acquired by Spotify in 2019, has a popular tech/culture franchise called Reply All, which in 2020 turned its attention to the inner workings of Conde Nast’s remaining food magazine, Bon Appetit. The series set out to explore the unequal advancement opportunities and discriminatory racial and cultural dynamics at the magazine. The first two episodes of Test kitchen were sharp, journalistically flawed, and wildly popular, amassing 8 million views in the series’ first weeks. (It took Serial five episodes to hit five million listens but that was 2014, before everyone—even your Dad—knew how easy it was to listen to podcasts.)

Then, Test Kitchen was cancelled and the remaining two episodes were shelved. The show’s producers came under fire for maintaining, as one Gimlet employee said on Twitter, a “near-identical toxic environment at Gimlet” as the one the series portrayed at Bon Appetit. They also accused Test Kitchen’s co-producers for helping squash the staff efforts to unionize as Spotify’s acquisition of Gimlet for $230 million.

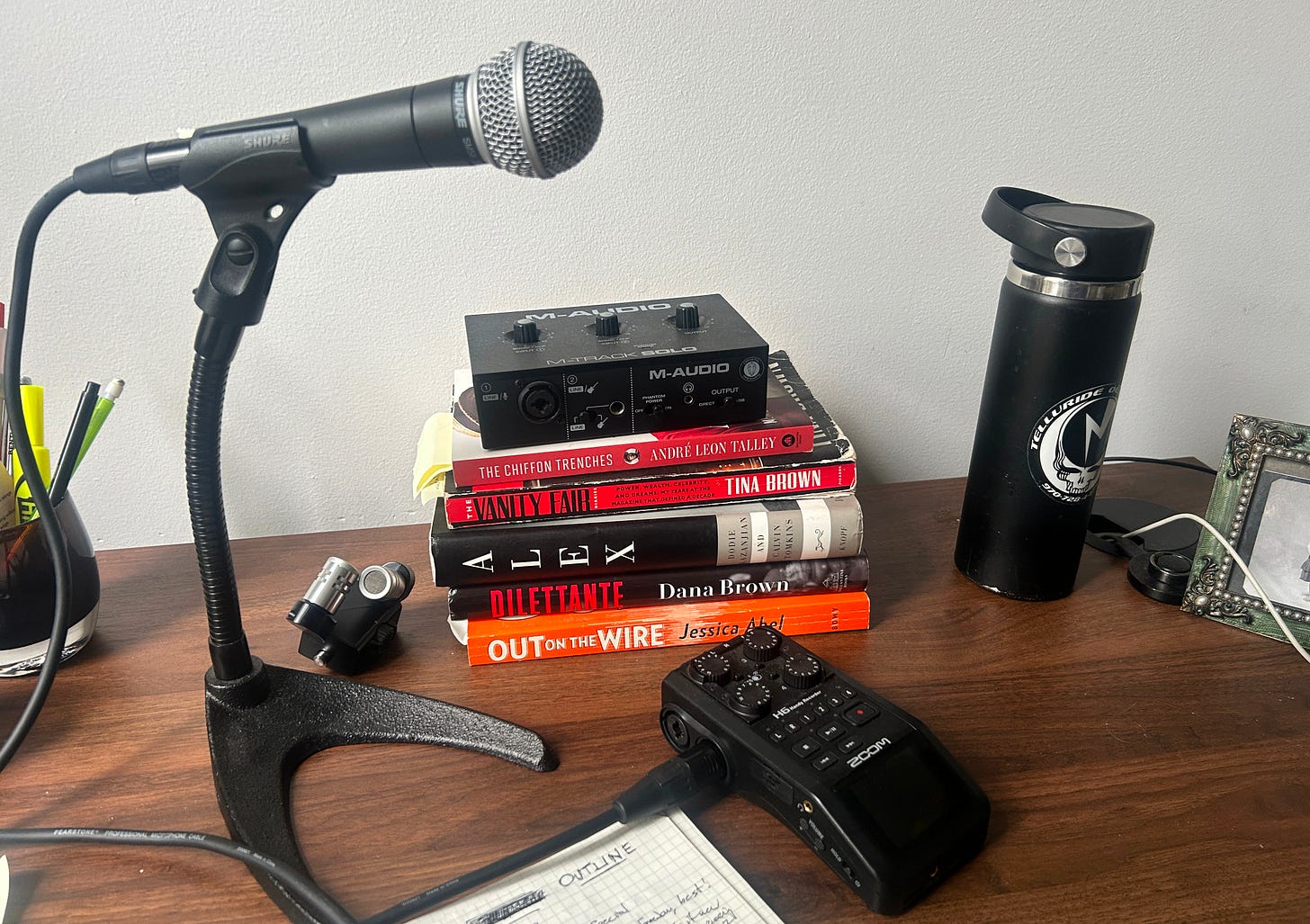

While my little series was still in a larval stage, I knew it would quite different from Test Kitchen. For starters, I didn’t have a tidy, preconceived narrative the way they did. My plan was to just hit record and let the conversation flow. The more people I talked to the more I realized how much I didn’t know about a place I worked for more than a decade.

The oral history style I had in mind had one one primary flaw within the fairly narrow conventions of podcasts:: it didn’t have an obvious A plot that movie people tend to talk about when they talk about structure. It was an oral history, which was a tougher series to sell. Some rejected it on that basis. “We need an A-plot,” I was told more than once. Another rejection was more candid: “No one here wants to tell another story about privileged white people.”

I took that as a hard no. And they weren’t wrong, but privileged white people was all I had at the moment. And I was still convinced that a story could be told about them and their manufactured privilege that ultimately did more good than harm.

So I emailed a guy who I knew would understand, a person who knew enough about the magazine world and 90’s nostalgia. Someone who understands the power of an oral history.

He said yes in the space of an hour.

His company would get the series produced and together we’d sell it to one of the big studios he’d sold series to in the past: Apple, Audible, Wondery, Spotify, iHeart, etc. They would chip in for studio time, though I’d also do interviews on Riverside and over the phone, help track down research clips, and pay me a fee.

They’d get half of whatever we sold the series for (minus expenses that they somewhat worryingly would calculate) and half of whatever subsequent series were produced or movies, TV, shows were made based on the IP.

“I think we should get Anne Hathaway to be the narrator” my new partner told me on one call.

At least he said he’d pay for studio time.

No matter. This was gonna be good. And everyone sounded amazing.

Next Episode: Great audio, sharp story-telling, dismal commercial prospects. Or go here.

.