How Not to Make a Podcast (Episode #3)

In the span of a month, I lost my job, the podcast market collapsed, and my production company laid off the guy who producing mine. But at least the tape is good.

My heart sinks all the time these days. After all, it’s officially the season of Conde Nast reappraisal. A new book. A new podcast. A new article. Someone will text me a link. “Did you see this?” And instantly my back gets hot, I toss my phone aside, and hurry away. To where, I don’t know. It’s inescapable. But the moment passes and I remind myself that I’m not alone in pursuing some version of the Conde Nast story. I get it. It’s a big, shiny, sugar-coated story and who doesn’t love a pastry?

Essentially what I tell myself is: Tough shit.

If things had gone differently—and you’ll see just how they went below—I would have had the series out a year or more ago. In fact, I’d be re-surfacing by now, engaging with loyal fans, posting their comments about how genius it is, people thanking me for getting it right, etc. But things didn’t go differently and now I’m relegated to the sidelines sitting on a full season of scripts and hundreds of hours of good tape.

The chorus of voices currently weighing in on Conde Nast, and on magazine nostalgia in general, has been trickling out for a while. I listened to a few episodes of Print is Dead (Long Live Print) which do pretty straight-forward single subject interviews with magazine vets, including some of the people I interviewed. And now, with the Vogue-centric Going Rogue with Jill Demling. And while the conversations are engaging and the subjects are right, they don’t amount to more than the sum of their parts. They don’t attempt to expand a collective central narrative the way I felt they could and should if done a different way.

Where those interviews would maybe include an aside about Conde Nast’s famous car and driver perk, the podcast I had in mind would include both the Editor’s thoughts on the car and driver that followed her around town, while also hearing from an assistant who abused the service, and then the Staten Island sales rep who landed the contract for Conde Nast in the late 70s, and who could tell us how much the company spent on it.

A listener could listen to an Editor in Chief talk about reading the New York Post every morning to make sure he hadn’t been fired overnight, and then hear from the media columnist who would be breaking the news in the Post.

And when I really started interviewing people, I saw that there was a through line, a larger narrative that made sense of the many different voices. It added up to something more than the sum of its parts. Or it would, if I could get it made.

And while I wasn’t interested in Conde Nast’s history, which has been told and will be apparently told again, it was a proclamation by Conde Nast himself that distilled it for me. In 1913, he wrote an article in The Merchants and Manufacturers Journal, called “Class Publication” that articulated a business strategy that lasted more than a hundred years and left the company spectacularly unprepared for the digital age. He wrote:

"A 'class publication' is a publication that looks for its circulation only to those having in common a certain characteristic… The publisher, the editor, the advertising manager and circulation man must conspire not only to get all their readers from the one particular class to which the magazine is dedicated, but rigorously to exclude all others."

That should come in handy, I thought, when I first read it. And it did. And what’s more, it supported what so many of my interview subjects had shared about working there, and the centrality of whipping up a fantasy of white middle-class luxury in their pages each month. It was that culture of exclusivity that was partly responsible for the company’s downfall a century later, it’s crisis of conscience in the summer of 2020, and its fatal non-embrace of the world wide web. (And no, it wasn’t because Si Newhouse fell asleep with his iPad.)

And if we’re speaking of business strategies, my personal one was deeply flawed, and marred by terrible timing. I’ll be brutally concise: No one who was about to lose their job (I was running content for a declining software company) was more confident in their future prospects than I was in the Spring of 2023. I had the Conde podcast in development and I’d been assigned a young, but talented producer to help put together the first episode.

At the same time my other podcast, City of the Rails, was cruising toward a second season. A knowledgeable friend had told me that a series with numbers like ours—we’d passed a half a million listens by then—was basically a shoe-in for renewal.

But this was the spring of 2023, a crucial inflection point in the podcasting business, when high wattage couples—Barack & Michelle, Harry & Meghan, Travis & Jason—were hauling in million dollar deals to interview people they admired, while the narrative series market dried up like a jellyfish on Florida asphalt. It’s as if everyone in the business woke up, looked around at each other, and said, “Hey, do you guys make any money from this shit?” And everyone said, “Nope. Not us. How ‘bout you?”

The week I got laid off, I heard from the young producer who was working on the first episode of the Conde series. He’d also gotten laid off. In fact, the production company got rid of just about everyone but the partners and whatever young person knew all the log-ins and how to process expenses. The Conde Nast project was on hold indefinitely.

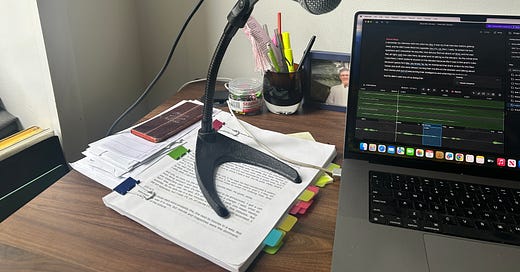

So now I had no job, no hope for a second season of the freight train podcast, and no prospects for this podcast. What I did have was time, a microphone, and a second kid starting college in the fall. So I kept interviewing people.

The other thing I had was a contract that prohibited me from doing anything on the series until my production partner (who was now essentially on life support) agreed to release me from the agreement. The deal had been: I’d do the wrangling, writing, and interviewing and they’d produce the podcast, which we’d then sell, splitting whatever revenue it received. Whenever I’d ask about a worst case scenario: What if no one buys it? Their answer was: We’ll just make it ourselves on the cheap and make it back on programmatic ads.

Now, their answer was: What do you want from me?

¯\_(ツ)_/¯

So I was legally bound to a company that had no interest in making the series I’d been working on for more than two years. They weren’t going to make it and they were going to make sure no one else could make it either. Their attitude was basically: “Fuck you. Sue me.”

Meanwhile, I knew Graydon was making progress on his memoir, and that the big Conde book was creeping toward publication because its author and I either interviewed or tried to interview the same people.

“You know there’s another guy doing a book like this right?”

“Yes, I know. The guy from the Times.”

“Yeah, that’s him. Do you have his email? Somehow I lost it and I want to clarify something.”

Again: Tough shit.

So now what do I do? Well, one answer would be to do nothing. More than a few people have suggested I just chalk it up to bad timing, take the loss, and stop wasting sleep over it.

That seems sensible, and wise, but it also feels wrong.

Another option is to wait for the market to return and then sell it. Almost everyone I know who used to make narrative longform podcasts, now sits in a studio while some former B-actress talks to their friends about menopause or celibacy or cold plunges. The market, safe to say, is not returning any time soon.

The third option is to learn a little Descript and start sharing some snippets of the 50 interviews I have with people who worked at Conde Nast at its peak (or serviced and reported on those who did). It would be a promotional gambit, not a trailer for a movie that doesn’t yet exist. What I’ll share is not central to what will be the real series, but rather ancillary, non-essential clips arranged in thematic clusters. I might call it Nasty Bits.

The first episode will probably be this:

Pushing Buttons, Throwing Shade: 27 Minutes About the Conde Nast’s Elevator [**that’s a working title, of course]

So it’ll be out soon on one platform or another, but will definitely be accessible here on Substack, where I’ll update you on my progress and also solicit advice. Tell me how it’s going and if you have any ideas on how to promote it. Please tell me what stories you want to hear. I have a lot of tape and I definitely take requests.

And yes, everyone sounds amazing.

Links to Episode #1

Links to Episode #2

Thanks, Chris. I guess if you say you're doing a three part story, you have to go ahed and do all three parts? Let that be a warning to you.

Solid